As all the world now knows, Harvard has selected Columbia’s Nirmal P. “Narv” Narvekar as the new head of Harvard Management Company.

His name had been bandied about as a prime candidate for weeks. We discussed it ourselves in our August 29 newsletter.

See: https://www.charlesskorina.com/harvard-management-company-size-really-matter/

Reportedly, a few big-endowment CIOs were not interested in the job. Fortunately, Mr. Narvekar was.

He is an exemplary investment manager and, for what it’s worth, we think Mr. Finnegan and his board made a good choice.

The Columbia endowment and its two amigos:

In 2002 Columbia University set up a new investment management company (CIMC) with its own board, and hired Mr. Narvekar as its founding president.

They plucked him from the University of Pennsylvania investment office where he’d been a managing director for four years, tasked with diversifying into private equity and other alternatives.

Previously, he’d spent 14 years with J.P. Morgan, including six years as managing director in their equity derivatives group. He’s a Phi Beta Kappa graduate in economics from Haverford College, and his MBA is from Penn’s Wharton School.

It’s a sterling resume, but people don’t hire resumes they hire performance and Mr. Narvekar’s performance numbers are outstanding, as we’ll see below.

And, we’re sure he’s been offered a salary commensurate with that performance. We’ll also discuss that important topic.

Shortly after he arrived at CIMC, Mr. Narvekar reached out to Peter B. Holland, an old colleague who had worked with him in JP Morgan’s derivatives group, bringing him in as chief investment officer. The two men have worked closely together for more than twelve years, and to excellent effect.

We were unsurprised to see Mr. Holland elevated immediately to the top job at CIMC as Mr. Narvekar departs. Despite all the talk about the importance of succession-planning, few organizations really have a proper successor on the launch pad. Columbia, fortunately, did; and we expect to see no hiccups in the organization they jointly built.

A makeover for HMC?

We (and many others) have written at length about Harvard’s difficulties and will spare you any more rehashing.

We had our say here: https://www.charlesskorina.com/harvard-endowment-hmc-time-reassess/

But the hire of Mr. Narvekar raises some obvious questions about the structure and direction of HMC going forward.

The previous two HMC presidents were hired under the aegis of the late James F. Rothenberg who chaired the HMC board until his sudden death last summer. It fell to the new chairman – Paul J. Finnegan – to run the search that found Mr. Narvekar. And the selection of a new president by a new chairman may involve more than just redecorating a single office.

Mr. Narvekar leads about 20 staffers at CIMC. When he arrives in Boston he’ll be greeted by over 200 HMC employees. That 10-to-1 ratio neatly underlines the situation he’ll be stepping into.

We think there will be at least some chipping away at Harvard’s “hybrid” model with its attendant high headcount, but probably not a revolution. We’re sure Mr. Narvekar and Mr. Finnegan have already discussed this unavoidable and delicate topic.

Remembering rule number 1:

One-year returns are statistically noisy and therefore more journalistically exciting. But much more weight should be put on the duller five- and ten-year annualized returns.

In this case, however, drilling down into 1-year returns will help highlight one of the important factors in Narv Narvekar’s performance at Columbia.

Here’s a comparison of Columbia to Harvard, Yale, and the average big (over $1 billion AUM) endowment for ten years.

Columbia endowment performance versus Harvard, Yale, and NCSE, 2007-2016:

fiscal yr-end |

Columbia (%) |

Harvard (%) |

Yale (%) |

NCSE >$1bn |

2007 |

23.1 |

23.0 |

28.0 |

21.3 |

2008 |

2.0 |

8.6 |

4.5 |

0.6 |

2009 |

-16.1 |

-27.3 |

-24.6 |

-20.5 |

2010 |

17.1 |

11.0 |

8.9 |

12.2 |

2011 |

23.6 |

21.4 |

21.9 |

20.1 |

2012 |

2.3 |

-0.1 |

4.7 |

0.8 |

2013 |

11.5 |

11.3 |

12.5 |

11.7 |

2014 |

17.5 |

15.4 |

20.2 |

16.5 |

2015 |

7.6 |

5.8 |

11.5 |

4.3 |

2016 |

-0.9 |

-2.0 |

3.4 |

NA |

NB: NCSE = NACUBO-Commonfund Study of Endowments.

CIMC outperformed HMC in every year but one (2008), however they beat Yale in only three years: 2009, 2010, and 2011.

In fiscal year 2009, as we all know, investors faced what Zorba the Greek called the Full Catastrophe. Nothing worked and everybody lost a ton of money.

Here we invoke Mr. Buffett’s famous dictum:

“Rule number one, never lose money. Rule number two, never forget rule number one.”

No one managed to follow Rule No. 1 in 2009, but Mr. Narvekar came closest.

Harvard’s drawdown was a horrendous 27 percent; Yale’s a slightly less horrendous 25 percent. By comparison, Mr. Narvekar’s pool lost a modest 16 percent.

In the eight years since 2009, Harvard has never managed to get their AUM back up to pre-crisis levels.

It was $36.9 billion in 2008, and just $35.7 billion as of June, 2016. The huge 2009 drawdown has been followed by mostly mediocre annual returns. AUM is still down 3 percent over 7 years despite their very successful fund-raising efforts.

Yale, on the other hand, got their AUM back up to pre-crisis levels in five years, by 2014. They had $22.9 billion in 2008, and are up to $25.4 billion this year. That’s an 11 percent increase.

But it was Mr. Narvekar who came closest to Rule No. 1.

CIMC was back above its pre-crisis AUM in just two years. They had $7.2 billion in 2008, and are now up to $9.0 billion this year: a 25 percent climb.

Columbia endowment growth in assets versus Harvard and Yale, 2007-2016:

fiscal yr-end |

Columbia ($bn) |

Harvard ($bn) |

Yale ($bn) |

2007 |

7.1 |

34.6 |

22.5 |

2008 |

7.3 |

36.9 |

22.9 |

2009 |

5.9 |

26.0 |

16.3 |

2010 |

6.5 |

27.6 |

16.7 |

2011 |

7.8 |

32.0 |

19.4 |

2012 |

7.7 |

30.7 |

19.3 |

2013 |

8.2 |

32.7 |

20.8 |

2014 |

9.2 |

35.9 |

23.9 |

2015 |

9.6 |

36.5 |

25.6 |

2016 |

9.0 |

35.7 |

25.4 |

If, instead of looking at 10-year returns, we consider just the period starting in annus horribilis 2009, we see that Columbia outperforms everybody because of their smaller losses in 2009.

In this table we use a 2015 cutoff so we can include the NCSE number.

Annualized endowment returns: 10, 5, and 7 years as of 2015:

– |

Columbia (%) |

Harvard (%) |

Yale (%) |

NCSE >$1bn |

10yr |

10.0 |

7.6 |

10.0 |

7.5 |

5yr |

12.3 |

10.5 |

14.0 |

10.4 |

7yr (2009-2015) |

8.3 |

5.6 |

6.8 |

5.6 |

On a 10-year basis, Columbia ties Yale and has a spread of about 2.5 percent over both HMC and the average big endowment.

Over 5 years they beat Harvard, but not Yale.

But it’s over the 7 years 2009-2015 where they really shone, with a 1.5 percent spread vs. Yale, and 4.1 percent vs. Harvard.

And, as this chart illustrates, Columbia’s returns look even better on a risk-adjusted basis.

Risk-adjusted returns as of 2015:

– |

Columbia (%) |

Harvard (%) |

Yale (%) |

NCSE >$1bn |

10yr Std Dev |

12.21 |

14.41 |

14.87 |

9.40 |

10yr Sharpe ratio |

0.79 |

0.52 |

0.68 |

0.41 |

CIMC has a lower standard deviation of returns than either Harvard or Yale, and a significantly higher Sharpe ratio.

Again, this is primarily explained by Columbia’s relatively smaller drawdown in 2009. The average big endowment was less risky in this period (with a smaller standard deviation of returns), but Columbia’s higher returns more than offset their higher risk, with a much higher Sharpe ratio than the average over-one-billion endowment.

CIMC allocations: out of the shadows:

CIMC traditionally says nothing about their allocations or their strategy. Reporters ask and they always get a polite “no comment.”

So, here we’ll try to throw a little light on what they’re up to.

CIMC has never published asset allocations, but some other offices at Columbia have sometimes alluded to them for their own purposes in obscure pamphlets. These may be “policy” rather than actual numbers, but we think they can be regarded as at least quasi-official.

Also, one can examine the university’s financials. With the coming of FASB rule 157 a few years ago auditors are obliged to offer a “fair-value” hierarchy table in the notes to the financials. This offers some clues about the components of the “investments” item on the balance sheet, even if it can’t be mapped neatly onto the assets in the endowment pool.

Here is a comparison of allocations for Columbia, Harvard, Yale, and the NCSE average on a “four-bucket” basis for fiscal year 2015.

Endowment Asset Allocations (%) “four-bucket” for FY2015:

– |

Columbia (%) |

Harvard (%) |

Yale (%) |

NCSE >$1bn |

Cash/ST/other |

3.0 |

0.0 |

2.8 |

5.0 |

Global equities |

26.0 |

33.0 |

18.6 |

37.0 |

Fixed income |

3.0 |

10.0 |

4.9 |

8.0 |

Alternatives |

68.0 |

57.0 |

73.7 |

50.0 |

total |

100% |

100% |

100% |

100% |

As we would expect, alternatives dominate these endowments as they have done for years.

Up above, we saw that CIMC’s 5-year returns were about midway between Yale and Harvard.

And, here we see that CIMC’s allocation to alternatives (68 percent) is also about midway between Harvard (at 57 percent) and Yale (at 74 percent).

All three have higher alts allocations than the big-endowment average, and all three beat the 5-year return for those other big endowments (there are about 94 of them).

It seems too simplistic to say that ranking of returns follows the ranking of allocation to alternatives. But these numbers are at least consistent with that notion, at least in this period.

Using clues in the financial statements we can try to break down Columbia’s alt allocation into its component parts. It’s our guesstimate, but we think it’s in the ballpark. Or you could call Narv and ask him.

This “six-bucket” chart uses our numbers for CIMC, and reported numbers for the others:

Endowment Asset Allocations (%) “six-bucket” for FY2015:

– |

Columbia (%) |

Harvard (%) |

Yale (%) |

NCSE >$1bn |

Cash/ST/other |

3.0 |

0.0 |

2.8 |

5.0 |

Global equities |

26.0 |

33.0 |

18.6 |

37.0 |

Fixed income |

3.0 |

10.0 |

4.9 |

8.0 |

Absolute return |

28.7 |

16.0 |

20.5 |

21.0 |

Private equity |

23.4 |

18.0 |

32.5 |

16.0 |

Real assets |

15.9 |

23.0 |

20.7 |

13.0 |

total |

100% |

100% |

100% |

100% |

Here we see that Columbia is midway between Harvard and Yale on private equity (including venture capital), but significantly higher in allocation to hedge funds. Columbia is significantly lower in real assets (including real estate) than the Yale or Harvard allotments.

We suspect that private equity is a strong driver of Columbia’s returns in this period.

If we could observe strong PE returns in other large endowments, we could reasonably ascribe similar returns to Columbia. Unfortunately, few endowments report annual returns by asset class. But a few do.

Harvard’s 5-year return to PE was 14.0 percent annualized as of 2015. But the much smaller UC Regents PE portfolio earned 17.5 percent annualized in the same period, and University of Virginia earned an excellent 22.9 percent.

Harvard’s 4-year return to PE as of 2015 was 11.1 percent. But the much smaller University of North Carolina (UNCIMC) earned 13.7.

We think it’s plausible that Mr. Narvekar (with his PE background) obtained PE returns closer to Virginia, Cal or North Carolina in this period. Combine that with his large allocation to the class and it probably contributed significantly to his outperformance vs. Harvard.

Compensation: Narvekar, Holland, Mendillo, Blyth, and Ettl:

For calendar 2013 (the latest available), the HMC president (Ms. Mendillo in her next-to-last year) earned almost three times as much as Mr. Narvekar: $9.5 million versus $3.5 million.

Her 2013 bonus was unusually large for reasons we can’t explain and Mr. Narvekar may not match it in any given period going forward. But we think it’s highly likely that his total comp in 2017 will be at least $7 million — double what he made at Columbia in 2013, and that is still a very handsome upgrade.

A big chunk of his comp each year has been deferred as incentive to stay at Columbia, vesting only in a subsequent year. We think he may forfeit around $3 million in banked pay when he departs. But his new contract with Harvard will no doubt make him whole.

Comp data for the most recent available three years is in the chart below and readers can draw their own conclusions.

We also note that Mr. Holland as chief investment officer at Columbia earned only about 10 percent less than his boss. We’re sure he will get a bump of at least that much as he moves up to the top job next year.

Mr. Narvekar will certainly be the highest-paid U.S. endowment chief by a wide margin.

Two other veterans will be roughly tied with Mr. Holland for second place: Mr. David Swensen at Yale and Mr. Scott Malpass at Notre Dame, who made $3.6 million and $3.9 million respectively in 2013.

Both Stephen Blyth and Robert Ettl have recently served as HMC president and CEO, the former for about 18 months and the latter for about 4 months and counting.

Their presidential comp is officially un-reported. But, we can guesstimate that Mr. Blyth was paid a Mendillo-sized salary with a base over $1.0 million and bonus in the range of $4 million to $8 million on an annualized basis. It’s not clear to us that Mr. Ettl, who has been serving on an interim basis, got a boost to that same level.

The latest published comps for Mr. Blyth and Mr. Ettl — as managing director and chief operating officer, respectively in 2013 — were $11.4 million and $4.0 million as detailed in our chart.

Compensation: Columbia versus Harvard

Narvekar and Holland versus Mendillo, Blyth and Ettl

(latest available data from tax filings)

Columbia (CIMC) |

Year |

Base |

Bonus |

W2 Total |

Narv P. Narvekar |

2013 |

$868,329 |

$2,623,753 |

$3,492,082 |

President |

2012 |

$847,887 |

$2,524,706 |

$3,372,593 |

|

2011 |

$825,878 |

$2,256,948 |

$3,082,826 |

|

|

|

|

|

Peter B. Holland |

2013 |

$782,075 |

$2,358,059 |

$3,140,134 |

CIO |

2012 |

$760,102 |

$2,269,040 |

$3,029,142 |

|

2011 |

$744,110 |

$2,028,397 |

$2,772,507 |

Harvard (HMC) |

|

|

|

|

Jane L. Mendillo |

2013 |

$1,195,068 |

$8,300,000 |

$9,497,390 |

Pres/CEO |

2012 |

$1,195,368 |

$3,550,000 |

$4,746,610 |

|

2011 |

$1,089,255 |

$4,187,102 |

$5,277,599 |

|

|

|

|

|

Stephen Blyth |

2013 |

$544,013 |

$10,890,869 |

$11,436,895 |

Managing Director in 2013 |

– |

– |

– |

– |

Robert A. Ettl |

2013 |

$765,987 |

$3,225,000 |

$3,993,000 |

COO in 2013 |

– |

– |

– |

– |

A new view:

For now, Mr. Narvekar labors on the 63rd floor of the Chrysler building in mid-town Manhattan. It’s America’s most elegant and famous Art Deco building, but, apart from the view, the CIMC offices are reportedly beige and utilitarian. However, they do have some excellent custom software running behind their computer screens.

According to a 2012 interview, Narvekar, Holland and their small staff had spent eight years developing a systems platform that enables them to efficiently gauge both the performance of their third-party managers and the endowment’s exposure to various asset classes.

“If we want to know how much risk a particular manager has taken, or how his returns rate against those of his peers in a particular market, we can compute that very easily and quickly,” said Holland. “If we need to determine how much risk exposure we have, say, in Europe, it’s remarkably easy for us to assess that and respond accordingly.”

We don’t know how much of that intellectual property Narv can bring to Boston, but it sounds like something worth emulating.

Narv is headed for HMC’s offices in the Boston Federal Reserve Building, a structure which resembles a giant concrete radiator.

However, tenants and their guests have exclusive access to the Harborview dining room on the 31st floor, with its spectacular view of the Bay.

Peroration: the long view:

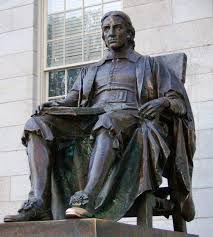

John Harvard, the son of a butcher; graduate of Emmanuel College, Cambridge; and emigrant to the New World; died of tuberculosis in 1638 at the age of 30. His maternal grandfather had been an acquaintance of William Shakespeare.

They called it consumption back then, and it was a slow death. The young clergyman had ample time to consider his legacy. He left half his money and all of his (even more valuable) books to a new college, the first in the English colonies. The little school was already more than a century old when John Adams matriculated there in 1750.

Four hundred years later, Mr. Harvard’s statue surveys the passersby in Harvard Yard while, across the river, his keystone gift, now grown to over $35 billion, sustains one of the world’s greatest institutions of research, scholarship, and teaching.

Narv Narvekar is just the latest in a long line of stewards. We think he’ll be a good one.