Saints, Sinners, and Foundation Money

by charles | Comments are closed07/31/2023

Yes, I’m paranoid–but am I paranoid enough? ― David Foster Wallace, Infinite Jest

While working on the “Skorina Letter” subscriber database last weekend, I came across an email address that gave me pause. A vague recollection. Something about the Maddox Foundation and a scandal regarding contested use of foundation assets?

Sure enough, turns out the case caused quite a stir a few years back and the intrepid team at the Magnolia Tribune diligently shared with their fellow Mississippians the mounting allegations and disclosures, including some rather salacious revelations thanks to the unsealed deposition of a former employee.

Nonprofit World’s more restrained report on the drama, “One Foundation’s Legal Battle: A Cautionary Tale for All Nonprofits,” added context and a few words of wisdom for their nonprofit readers.

The combatants included Ms. Robin Costa, former secretary and treasurer of the foundation who became, upon the Maddoxes’ untimely death, president and arbiter of the foundation’s one-hundred-million-dollar bequest, a battalion of lawyers, judges, prosecutors, and witnesses, one state district attorney general, and a former Mississippi governor.

Litigation raged across state lines with accusations of gross mismanagement, high living, and double-dealing hurled back and forth among the adversaries.

It’s probably best to let the Magnolia team take it from here. (See the above links and one more Magnolia item here.) But in the end, the foundation clawed back about half the assets.

The moral of the tale? When it comes to money, there are very few saints. There are good reasons for strict board governance, robust financial controls, and established public disclosures.

Which brings us once again to the subject of professional money management. If you can afford to fund and build an internal investment team and layer on the checks and balances, that’s great. We’re here to help.

But once donors set up a foundation or endowment it can get complicated, as the Maddox case illustrates.

The outsourced chief investment officer industry is growing for a reason, cost-effective available professional investment management with institutional grade controls and processes, and third-party fiduciaries with watchful eyes on the money.

As we wrote last week in our OCIO summer update, most nonprofits and families (basically anyone under $500 million in investable assets) just don’t have the time or resources to build competitive and secure internal investment capabilities. The OCIO solution is an effective alternative.

— Charles Skorina

Read More »OCIO update, Summer 2023: Holding On

by charles | Comments are closed07/08/2023

The best way to predict the future is to create it. ― Unknown

Our summer 2023 Outsourced Chief Investment Officer (OCIO) update features 101 firms, each with a designated contact individual and helpful hints to reach them: name, title, email, and phone number. It’s the most comprehensive, accurate, and accessible available.

Our goal is to help families and institutions locate, review, and connect with full-service discretionary outsource investment managers. As Henry Kissinger supposedly quipped when pondering a question on European leadership, “If you want to speak with Europe who do you call?”

The companies on our list care deeply about their customers. Our directory makes it easy for prospective clients to reach them.

Holding On

For the year ending December 31st, 2022, OCIO providers managed to hold the line against volatile financial markets and investment headwinds, our new era of uncertainty to quote McKinsey.

Despite the Nasdaq losing a third of its value, 33%, the Russell 3000 down by 20.48%, the S&P 500 off 20%, and the Dow shedding 9%, total outsourced assets on our list dipped a tenable 9.5%, or $356 billion to $3.4 trillion.

It’s not all Strum und Drang, however, both Cerulli Associates’ OCIO Survey 2022 and Capgemini’s Wealth Management Top Trends 2023 expect healthy demand for OCIO services in the years to come.

According to Capgemini, “The growing complexity of assets, the necessity to adjust to volatile markets and uncertainties, access to experts, and shrinking investment management costs will heighten the profile of OCIOs.”

This is a common refrain from clients and contacts. It’s expensive to support an institutional grade full-service asset management platform and it will only get worse. Costs are climbing for infrastructure, cyber-security, regulatory audits and compliance, and access to liquid and alternative products and managers.

Given these challenges, there are only three ways most wealth and institutional money managers will grow — buy, sell, or merge.

This is just as true, by the way, for RIAs, which explains why so many are snuggling up to better resourced competitors. Echelon Partners 2022 RIA M&A Deal Report tracked 340 announced transactions in 2022 alone, the tenth straight year of record acquisitions

The Gang of Eight

At year end 2022 eight firms – Mercer, BlackRock, Russell Investments, Goldman Sachs, SEI, AON, SSGA, and WTW – managed about 52% of the total AUM on our list. These eight providers with their size and resources dominate the largest segment, corporate pensions.

But the corporate defined benefit business is a land unto its own, actuarial, regulated, and liability driven, with big-ticket AUM on offer, $1.78 trillion among the top 100 US plans. In 2022, for example, BlackRock added $56 billion worth of new business from just two accounts, the $14 billion General Dynamics pension and the $42 billion Teamsters Central States Pension Fund.

Eight largest OCIOs by AUM

Read More »Family Office Investors: getting paid to wait

by charles | Comments are closed06/21/2023

Follow the money, always follow the money – William Goldman, “All the President’s Men”

Bob Dylan wrote the evocative The Times They Are a-Changin’ in 1963, and sixty years later the song might just as well be a meditation on today’s unsettled times.

While large institutional funds – pensions, sovereign wealth funds, endowments – continue to invest as if nothing has changed, our family office clients are preparing for a more nuanced and conflicted scenario, building liquidity and waiting for clarity.

Changing times

After a 2,000-basis-point decline in interest rates between 1980 and 2020, the Federal Open Market Committee on March 16, 2022 finally changed the game and began the process of lifting their price controls on money.

“Nowadays,” writes Howard Marks, “the ICE BofA U.S High Yield Constrained Index offers a yield of over 8.5%, the CS Leveraged Loan Index offers roughly 10.0%, and private loans offer considerably more.”

“In other words, expected pre-tax yields from non-investment grade debt investments now approach or exceed the historical returns from equity.”

And as Marks postulates, not only has the “sea change” in rates finally put an end to our golden era of free money, it also quite possibly signals the end of private equity’s buoyant forty-year run.

“Almost the entire history of levered investment strategies has been written during a period of declining and/or ultra-low interest rates.”

Along the watchtower

One of our family clients recently asked his private banker at Citi what he saw other large family offices doing. The banker’s answer, “going to cash!”

The latest Goldman Sachs 2023 Family Office Investment Insight Report surveyed family sentiment and found that “since 2021, global family offices, on average, increased their combined allocation across cash and fixed income from 19% to just over 22% total — 12% in cash and cash equivalents, and 10% in fixed income.”

This move to liquidity and safety is hardly surprising. As we wrote a year ago, family offices have been around for centuries and weathered every conceivable storm.

From the major-domos in ancient Rome to Rockefeller and Microsoft heirs, cash has always been king. Liquidity meant power and the means to act in good times and bad.

Maybe it’s also because family founders are usually operators who run businesses and in business, running out of cash is an original sin.

The clarity of hindsight

So, how are the nation’s largest pensions, the really big money boys and girls ($5.19 trillion in DB assets), dealing with this historic “shift?” As nearly as we can tell, they don’t have much room to maneuver.

They’re still boosting their allocations to private markets despite massive amounts of dry power, intense competition, increasing rates, decreasing returns, and make-believe marks.

The $442 billion CalPERS pension, for example, announced in January that the allocation to private equity would be increased from “8% to 13% starting with the 2022-23 fiscal year.”

Even if pensions wanted to alter course, however, they face performance pressures and institutional roadblocks. Not to mention funding commitments and low liquidity.

Changing course means educating boards, building expertise, and overcoming vested interests, an unpleasant and for now unlikely process. But with a snowballing funding crunch, something will eventually give.

To quote John Kenneth Galbraith, “There can be few fields of human endeavor in which history counts for so little as in the world of finance.”

Fixed income, how sweet it is

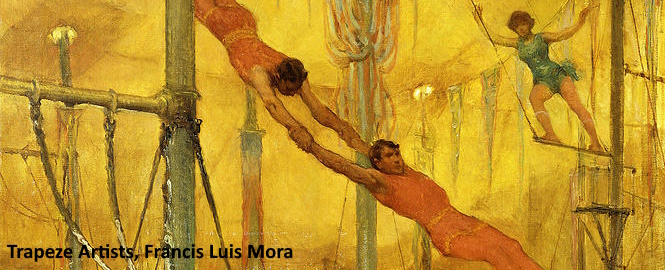

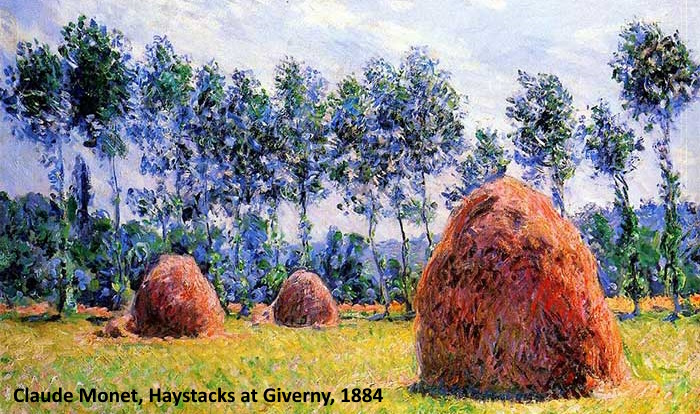

Read More »Headhunters and Haystacks

by charles | Comments are closed06/03/2023

“Don’t look for the needle in the haystack. Just buy the haystack!” — John Bogle

If it’s hard picking superior investments and asset managers, on what basis should we select the investment officers who pick those managers?

Take public markets, for example. According to Jason Zweig, Investing Columnist for The Wall Street Journal, “only 4.3% of stocks created all the net gains in the U.S. market between 1926 and 2016.”

In other words, over the last ninety years, less than two hundred stocks returned legendary money to their investors.

Zweig maintains that finding these “superstocks,” as William Bernstein of Efficient Frontier Advisor calls them, stocks that rise in value by 10,000% or more, is for most folks a losing proposition. He has argued for years that investors are better off buying a broad-market index fund.

What about private markets?

Private markets have their own challenges. A study by ULU Ventures concluded that venture capital firms “pick winners only 2.5% of the time. More than a decade of data reveals that out of more than 4,000 VC investment rounds annually, the top 100 generate between 70% and 100% of industry profits.”

The odds aren’t much better across buyout firms. The Oregon Investment Council pension system has invested in private equity for years. They are experienced, savvy, and comfortable with the asset class.

But over the last ten years the staff would have been better off putting their PE allocation into the Russell 3000. For the ten-year period ending December 31, 2021, their PE investments returned 15.7% versus 17.1% for the R3000, underperforming their benchmark by 4.3%.

Serious investing is about consistency

In our interview with Jon Hirtle, executive CEO of Hirtle Callaghan, he described investing this way. “Serious investing is about consistency, and serious investors position their portfolios to succeed in a highly uncertain future.”

How uncertain? Since 1945 the S&P 500 index has grown on average 11.12% per annum but during this span there have been 14 bear markets with drops averaging 32%.

And yet, the best CIOs somehow find a way to outperform – Paula Volent and David Swensen for example. Ms. Volent, Bowdoin College chief investment officer from 2000 to 2021 and current CIO at Rockefeller University, has topped our charts for years, delivering 11.9% for the twenty-year period ending June 30, 2021, and 14.5% for the last ten years.

And David Swensen, a seminal figure in the investment industry, produced a 13.7% per annum return over his thirty-five-year tenure as CIO at Yale.

Searching for the next Volent

For us, the search process begins with two questions.

The first is data driven. After years of evaluating investment talent for families, nonprofits, and asset managers, we look for persistence along with performance in a candidate’s background.

Our pool of talent includes hundreds of endowments, foundations, public and private pensions, health systems, associations, and charities, another five hundred to a thousand family offices, and thousands of OCIOs, RIAs, and for-profit asset managers.

It’s a deep bench but consistent performance is the key. And it’s not always apparent who’s driving the process.

Every candidate tells us they find great managers and pick great stocks. They all, apparently, produced top quartile results.

But, over time top chief investment officers stay on top. It’s in our data.

The second question is based on intuition and experience. Is this candidate someone that catches our eye? Piques our curiosity? An overachiever? We look for soft skills that indicate leadership and accomplishment.

Five key attributes in winning candidates

Read More »Succession and the Business of Money

by charles | Comments are closed05/02/2023

If I thought all I could achieve over the next ten years was 13 percent annual growth I’d junk my company and start over. – Anonymous Founder

Sooner or later most successful businesses lose the founder’s intensity and vision, and attention eventually shifts to the mundane business of making money.

Founders grows old, the heirs lose interest, marriage, divorce, and death intervene and before they know it all that’s left are trusts, dividends, and decline.

It doesn’t have to be that way. Some families stay on top for centuries. A Bank of Italy study a few years back found that many wealthy Florentine families have stayed wealthy for 600 years.

And a recent IMF paper concludes that “for given portfolio allocation, individuals who are wealthier are more likely to get higher risk-adjusted returns” and “high returns both bring individuals to the top of the wealth scale and prevent them from leaving it.”

Education, culture, and entrepreneurial talent all play a part and an internal investment office for UHNW families may help promote generational alignment and cohesion.

As professor Mandy Tham at the Singapore Management University writes, a constructive family office can serve as a forum where the generations can negotiate and agree on investment goals and legacy.

But building a family investment office to last is not easy. Too many family heads confront what Noam Wasserman, professor, author, and dean of Yeshiva University’s Sy Syms School of Business calls the founder’s dilemma.

Founders who want to manage empires will not believe they are successes if they lose control, even if they end up rich. Conversely, founders who understand that their goal is to amass wealth will not view themselves as failures when they step down from the top job.

Family office confidential

What some founders and CIOs really think about building and running an investment office.

A family office investment operation will never earn as much as the family business, so why have one?

The business of money management is all about risk mitigation and wealth preservation and first-gen founders aren’t usually built that way.

A notably successful individual had this to say after we showed him our latest 10-year Endowment Performance Rankings a few weeks ago.

Keep in mind that these are terrific returns for diversified, multi-asset, global portfolios and these CIOs are the best in the business.

Bowdoin and former CIO Paula Volent topped the charts with a 13.3 percent return, MIT and Seth Alexander finished a hair’s breadth behind at 13.02, Brown and Jane Dietze ranked third with 12.3, and Princeton and Andy Golden fourth at 12.2.

After studying our rankings and returns, he paused for a moment and then said “Charles, if I thought all I could achieve over the next ten years was 13 percent annual growth I’d junk my company and start over.”

[The average return by the way, for our pool of one-hundred endowments over one billion dollars AUM, was 9.2 percent with a mean of 9 percent.]

I don’t want a chief investment officer looking over my shoulder.

Jon Hirtle, co-founder of Hirtle Callaghan, has been managing family and institutional money for almost forty years.

We asked him why successful founders don’t always see eye to eye with endowment style chief investment officers and here’s his reply.

Read More »