Foundation Chief Investment Officers and the American dream

by charles | Comments are closed04/28/2017

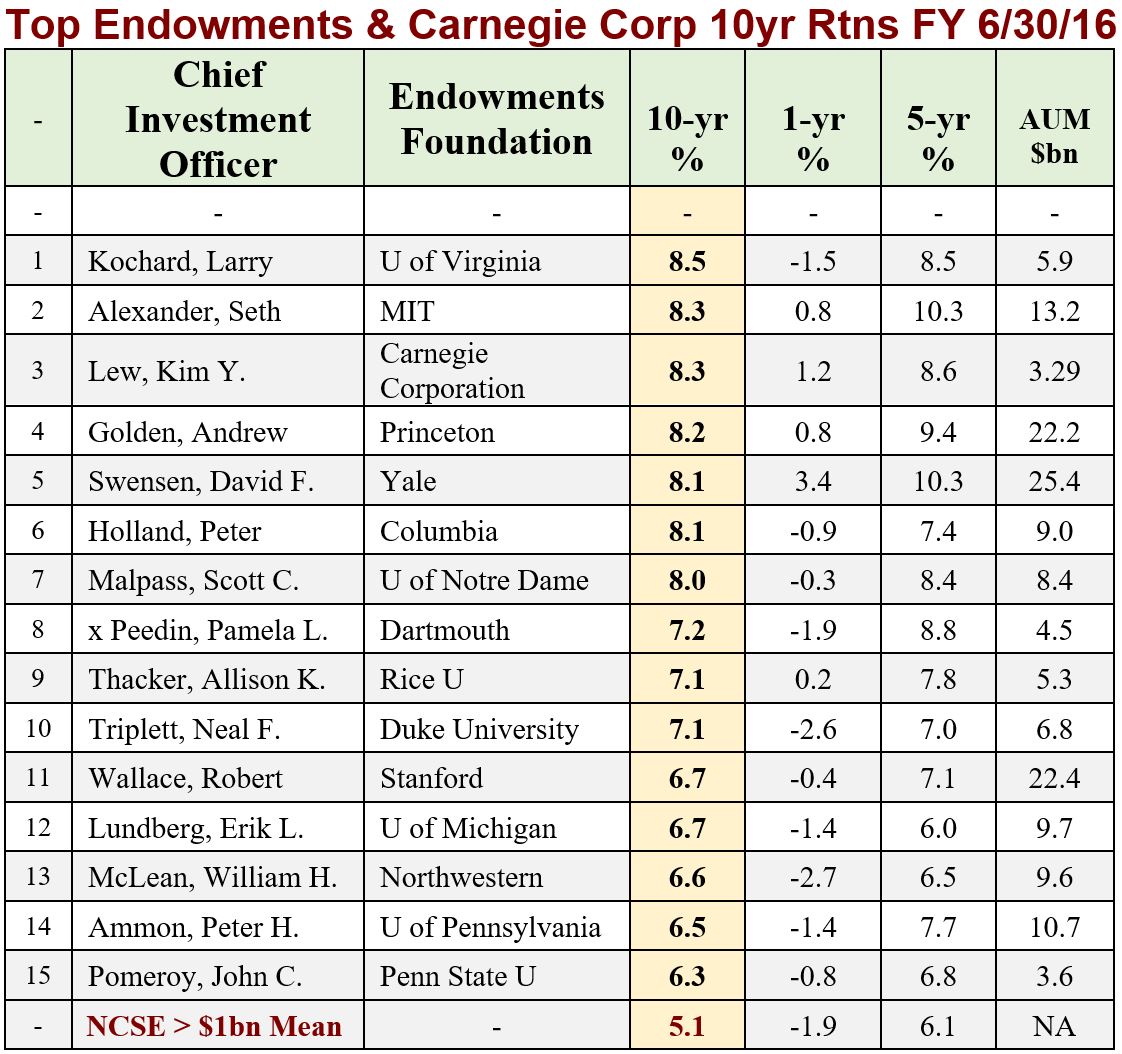

Our March letter focuses on the venerable foundations of New York City and one of their most accomplished investment pros: Kim Y. Lew, chief investment officer of the Carnegie Corporation.

We have an in-depth conversation with Ms. Lew on her career in foundation investing and the future of women and minorities in her field. We also look at pay and performance in the NYC foundations, with some illuminating charts for our quant readers.

Our friends at the Foundation Center tell us there are 243 American foundations with over $1 billion in assets and New York City harbors 31 of them, including some of the biggest and most storied. The money wasn’t all made there, but it tended to flow toward Manhattan because that’s where the money-managers were.

According to David Swensen, “a deep appreciation of history” is essential to an investment professional. Not just knowledge, mind you; but appreciation. History may have temporarily put that money in their care, but markets and circumstance are always threatening to take it back.

Goethe’s Faust got it right when he declaimed:

“That which thy fathers have bequeathed to thee, earn and become the possessor of it!”

Mr. Carnegie and Ms. Lew:

When Andrew Carnegie endowed the corporation with $125 million in 1911 – perhaps $3 billion in 2017 dollars – he founded the largest charitable entity of its day. Along with the creation of the Rockefeller Foundation in 1913, this marked the beginning of the modern era of foundation philanthropy.

The Carnegie Corporation, headed by the eminent Vartan Gregorian, marked its centenary in 2011, the year Kim Lew became co-CIO, and it is still among the twenty-five largest foundations in the U.S.

Despite continuing to give away at least $150 million every year (5% of net investment assets), the Corporation’s endowment is larger today – in constant dollars – than it was in 1911. This is due in part to the forbearance of America’s taxpayers via the Internal Revenue Code, but also in large part to the skill of Ms. Lew, her colleagues, and their predecessors in maintaining impressive investment returns over the generations.

Read More »What makes a great chief investment officer?

by charles | Comments are closed04/20/2017

What makes a great chief investment officer?

All professional investors want to make money. The question is, how and for whom?

In the for-profit world of Wall Street asset managers and retail mutual funds, the differences among managers reflect investor appetites, time horizons and risk tolerances. They must all serve their customers, or the customers will walk. But they are also profit-seekers, motivated by bonuses and the bottom line.

Most chief investment officers start their careers as traders, analysts, or consultants; working with spreads and price dislocations, capital structures and cash flows, or advising on asset allocations and manager selection. Ex-traders like Sam Gallo, CIO at the University System of Maryland, are particularly valuable now, because they know how to move large books quickly and cut transaction costs, topics of keen interest these days.

Eventually, some find their way into the family office and non-profit world of multigenerational, multiasset investing, researching opportunities and managers in public and illiquid markets.

Dedicated family office CIOs – between 800 and 1500 in the US – invest in anything and everything; in stocks, bonds, loans, cold storage, tankers, and toll roads. But tax implications become a priority; and family preferences – rational or not – drive the portfolio.

CIOs work at the pleasure of a complex and opaque authority whose circumstances, mood, location, and needs are subject to change at any time. In the family office world, one often has no idea how much liquidity is required as family purchases can be large, lumpy and unpredictable.

Both Alice Ruth and Jason Perlioni jumped to endowment CIO positions this year after long stints at family offices; Ms. Ruth moving to Dartmouth after nine years at Willett Advisors (Michael Bloomberg) and Mr. Perlioni moving to Johns Hopkins after ten years at the Pritzker Group.

Working for a family office can be an attractive and rewarding experience, but all family office CIOs understand Leo Tolstoy’s famous line from Anna Karenina, “All happy families are alike; each unhappy family is unhappy in its own way.”

Managing assets for tax-exempt Institutions differs from all the above.

Some institutions prioritize wealth creation while others prioritize transparency, political accountability, and risk minimization. Endowments, foundations, hospitals, cultural institutions, corporate and public pension funds can fall into either group.

In each case, however, the CIO job is what one makes of it; some are delegators, some are micro-managers, and some are just liaisons between a consultant and an investment committee.

Corporate and hospital chief investment officers structure their portfolios primarily to manage risk. Corporate CIOs are liability driven and have a financial mindset. They think in terms of payouts, terminal value, and matching durations. They care less about outperforming peers because absolute return is seldom their top priority or that of their boards. Bill Hammond, the CIO at AT&T and Jason Klein, CIO at Sloan-Kettering NYC, understand the mission of the institution; their job is to minimized liabilities and forestall surprises.

The “endowment model” of fund management prescribes a highly diversified portfolio of investments across public and private markets. Most endowment and foundation CIOs strive to earn the best possible risk-adjusted returns and grow the corpus over decades.

Read More »