The mysterious shortfall in women chief investment officers

by charles | Comments are closed05/06/2019

In our last newsletter we looked at the number of women CIOs at big endowments*. Among 109 North American endowments over $1 billion we identified 20 (including one female director of investments and one CFO who liaises with their OCIO providers).

That’s just eighteen percent – less than one out of five.

For this issue we also took a look at the mid-sized schools (in the $500 million-to $1 billion bracket), to see if the situation is any better.

Unfortunately, that’s a no. We found 10 females among 85 schools. That’s just 12 percent – a significantly lower representation that among the bigger schools.

We’ve inserted a chart below with the CIOs ranked by AUM.

Twelve percent in this group is not quite as bad as it sounds. That’s because mid-size endowments are less likely to have dedicated in-house investment staff – either men or women.

Many prefer to outsource, or to use a committee-and-consultant model without an internal investment office.

But it’s still not a great number.

Although we haven’t done an exact count, we should note that females are well represented among professional slots at the major OCIO firms and consultants. These are good jobs, and often a gateway to CIO jobs (although they usually don’t pay as well).

This may somewhat mitigate the overall situation for women jobseekers.

Charting the trend

That’s the static picture, but the trend is even more important.

Is that gap worsening, or about the same over recent years?

Unfortunately, it seems to be widening.

Looking at recent turnover, 9 departing female CIOs have been replaced by men; while only 3 were replaced by other women.

Just one departing male was succeeded by a female.

These turnovers are detailed in the next chart.

Read More »Ranking top colleges by 5-year returns

by charles | Comments are closed04/17/2019

In February we published an abbreviated list of five-year endowment performance for fiscal year end June 30, 2018 for 61 schools to compliment the release of the annual NACUBO TIAA study. Today, we introduce our big list with one hundred large endowments.

Every CIO on our list is experienced, dedicated, and adept at running a diversified portfolio. But MIT produced a five-year return of 12 percent while the University of Chicago posted 6.87. Why the divergence?

Different institutions, different goals

Every school has its own endowment payout rate and tolerance for risk. Some schools rely heavily on income, others place more weight on growing the principal.

It takes years to fully implement a multi-asset, multi-generational investment strategy and altering course mid-stream – a new investment chair? a change in CIOs? – can sap performance for a decade.

The challenge for the board and chief investment officer is to maintain course when market fluctuations shake conviction and crowd psychology rattles trustees.

Most high-performance institutions on our list have stable boards and long serving chief investment officers. See: A College Investor Who Beats the Ivys.

Happy boards, happy staffs

The personalities, preferences, and experiences of board members interact in a variety of ways, usually good, sometimes bad, and occasionally incoherently. The trick is to figure out how to work together, achieve a consensus on investment policy, and let the staff handle the investing.

#1: No surprises

Serving on a nonprofit board has many upsides; personal satisfaction, peer recognition, and an opportunity to make a difference. But when things go wrong, the reputational risk is brutal.

No board member at Michigan State or Southern Cal could have foreseen the scandals that erupted on their watch. And we wrote at length about past challenges at the Harvard endowment. It takes a long time to dig out from under poor management as the current board and CEO/CIO can attest.

The job of the investment staff is not to beat Yale, it’s to meet the objectives set by the board.

Read More »Nonprofits gird for tough new tax rules

by charles | Comments are closed03/13/2019

We’re executive recruiters, not lawyers, so you generally won’t catch us opining on important lawyerly stuff like detinue, replevin, trover; or even usufruct (especially usufruct). We’ll leave all that to the learned JDs.

But, in our daily conversations with investment heads in the nonprofit investment world, we’ve been getting an earful about the latest Congressional tax edicts which will make hiring senior executives much more expensive.

The Bare Bones

The 2017 Tax Reform Act fills 500 pages of small print. It has some good points and bad points apart from lowering individual and corporate tax rates, which got all the public attention.

Under “good,” it lowers the excise tax on beer to $16 per barrel. No problem there.

But, under “not so good” are two sections pertinent to the heads of college endowments, and to nonprofit organizations in general. Those include charitable grant-makers, symphonies, museums, hospitals, and many other charitable entities.

The first (Code Section 4968) imposes a 1.4% excise tax on the net investment income of certain private colleges and universities. We had our say about this elsewhere.

The Yale Tax, as it might be called, will raise a risible $1.8 billion over ten years.

Calling this a drop in the bucket would be an insult to drops and buckets. It’s $180 million annually in a $3.8 trillion U.S. budget and strikes us as a political gesture which raises virtually no money and accomplishes no practical purpose, even for people justifiably aggrieved about college costs.

The second section (Code Section 4960) is what nonprofits generally – not just colleges – are alarmed about as it begins to kick in this year, because it will raise the cost of hiring senior employees.

We recruit nonprofit investment heads and advise boards on compensation and performance. So, any tax that makes hiring chief investment officers and other executives more expensive and complicated gets our attention.

More broadly, it makes it harder and more expensive for these charities to carry out their missions, which should concern everyone.

Section 4960 imposes an excise tax on “excess” executive compensation at tax-exempt organizations.

Congress has decreed that any non-profit employee compensation exceeding $1 million is “excess.”

The tax will amount to 21 percent of the so-called “excess” compensation, and it will pertain only to the five highest-paid employees.

Chief investment officers – and CEOs, and football coaches – will be relieved to know that the tax will be levied on the employers, not on the employees.

But, it will obviously have a knock-on effect on how much they can afford to pay new hires, or how big a raise they can offer talented incumbents to help keep them aboard.

Some wag has referred to this as the Nick Saban Tax, in honor of the redoubtable Alabama football coach. Coach Saban is said to be the highest-paid college coach in the country at $8.3 million in 2018.

Coach Saban is well known, and so is his compensation, at least among Southern Conference fans. But there are more obscure execs also in the cross-hairs, e.g. Anthony Tersigni, CEO of the huge Ascension Health system in St. Louis, who earns even more. He takes home $17.5 million, and a few other nonprofit healthcare execs were also up in the 8-digit range. (The Act explicitly excludes practicing physicians, who are often the highest-paid people in these organizations.)

It looks like Ascension will be on the hook for at least an extra $3.5 million annually just to keep Mr. Tersigni.

We estimate that the celebrated Yale chief investment officer David Swensen is currently making about $6 million. And we think the average CIO among big endowments now makes about $2 million.

All three of these gentlemen are among the very best in their respective professions, and they are arguably worth every penny of their – admittedly handsome – salaries.

Let’s do the math for Mr. Saban: 8.3 minus 1.0, times 0.21, equals 1.5. So, Alabama will have to budget for at least an additional $1.5 million yearly. That’s a budget item they hadn’t even thought of just a year ago.

The Wall Street Journal has counted 2,700 nonprofit employees (not just at colleges) who were paid over $1 million in 2014.

Read More »Latest 5-year Endowment Performance

by charles | Comments are closed02/07/2019

Five-year endowment performance:

Behind the NACUBO numbers

This February has been a rough one for weather in much of the USA, but two events this month should bring a little sunshine our way.

First, NACUBO rolled out their annual endowment study: the semi-official league tables for endowment investors. Then, next week, NACUBO and TIAA will host their conference in New York where presenters and attendees will ponder the numbers.

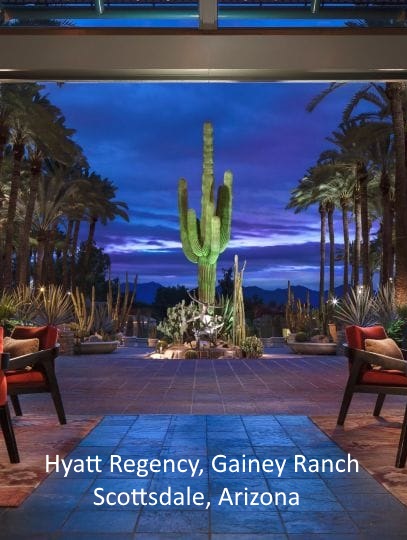

In between, we have Nancy Szigethy’s always engaging NMS Investment Forum in Scottsdale, Arizona. It’s at the Hyatt Regency Gainey Ranch, February 9-12, 2019 – an event which draws top endowment and foundation leaders for camaraderie and Arizona sunshine.

Scottsdale is only a quick drive up the I-10 from our new home in Tucson. So, if you’re planning to attend NMS, shoot me an email at skorina@charlesskorina.com and say hello. You never know which Hyatt lounge I might find myself in this weekend.

————————————————–

Endowment performance: a few observations

Our SEER report (Skorina’s Enhanced Endowment Report) is enhanced because we disclose performance of individual endowments, which NACUBO is not permitted to do.

This update offers 5-year investment returns for 61 endowments for FY2018. We consider the 5-year return the most meaningful for comparing the performance of endowments and their chief investment officers.

We’ll publish our complete list of CIOs and more detailed commentary when all the returns are in and computed by our clever but overworked staff.

We recruit chief investment officers for a living, so we avidly follow all the US universities and colleges with AUM over $1 billion (and many with less) – and we advise board members, families, and management on investment performance and executive compensation.

Where are the women?

Considering the number of highly-qualified female investment professionals we encounter every day, they are still a distinct minority in the top jobs. Something is obviously not working in the hiring and promotion process.

Our SEER list below includes 15 women among the 58 individual (non-OCIO) chief investment officers.

That’s 26 percent, which doesn’t sound too bad. But the picture is much worse in the larger universe of big-endowment CIOs. There, the percentage is only about 15 percent, and that’s down over recent years.

But we can at least highlight those 15 in their own list, which we’ve added down below.

Read More »Family Wealth: Finding Purpose, Fighting Entropy

by charles | Comments are closed01/15/2019

It is better to have a permanent income than to be fascinating.

– Oscar Wilde

A conversation with Stuart Lucas: wealth manager, educator, and family scion

Stuart Lucas has double-barreled credentials as a wealth manager.

He’s a Harvard MBA who worked for years with top-shelf financial firms including Wellington Management Company and Banc One (now JP Morgan Chase), where he led their Ultra HNW unit.

And, he is himself an heir to family money by way of his great-grandfather, E. A. Stuart, who founded the Carnation Company. In 1985, the closely-held business was sold to Nestle, and the proceeds were distributed among Mr. Stuart’s descendants.

In 2004, Mr. Lucas merged his professional and personal worlds by founding Wealth Strategist Partners, which continues today as the investment advisor to his and selected other family offices.

He has gone on to design and lead a Private Wealth Management executive education program, designed specifically for wealthy families at the University of Chicago Booth School, now in its 12th year. And, as an adjunct professor, he has taught a Wealth and Family Enterprise Management course at the MBA level.

All this experience has also been distilled into his widely-read book, Wealth: Grow It and Protect It, for general readers; and into academic-quality papers for The Journal of Wealth Management.

We’re delighted that he made some time to talk to us.

Keeping it in the family

Skorina: Stuart, you’ve focused on high-net-worth families and their money for decades as a practitioner; an academic; and even personally, as a member of an extended, affluent family. You probably know as much about this stuff as anyone in the business.

Where do you begin with a new client who has to deal with all of this for the first time?

Lucas: Charles, it’s true I’ve been doing this for quite a while, but no one knows everything about it. I learn something new every day.

A family office with significant wealth has many moving parts. There’s money-management per se, which you focus on; and it’s crucial.

But, there are also the structural, legal, and tax issues. And there are opaque but vital intra-familial and cultural issues that have to be dealt with. They’re all important, and all inter-related.

The laws and tax rates keep changing, so do markets, and so do the families themselves. We try to design and execute an integrated strategy that balances all these elements.

Skorina: So, how do you start the conversation with a new client?

Read More »